Area History

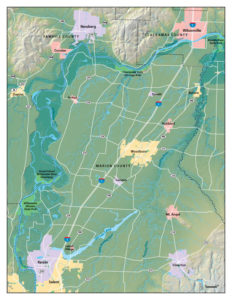

Friends of French Prairie French Prairie is a term dating back to the 1820’s and is most typically used to describe the area of the Willamette Valley bounded on the west and north by the Willamette River, on the east by Canby and the Molalla River, and extending down through St. Louis and Gervais toward Salem. Thus, it includes Champoeg State Park and Historic District, the historic towns of Aurora, Donald, Butteville, Gervais, Hubbard, St. Louis, St. Paul and Woodburn, and a number of French Prairie historic churches.

French Prairie is a term dating back to the 1820’s and is most typically used to describe the area of the Willamette Valley bounded on the west and north by the Willamette River, on the east by Canby and the Molalla River, and extending down through St. Louis and Gervais toward Salem. Thus, it includes Champoeg State Park and Historic District, the historic towns of Aurora, Donald, Butteville, Gervais, Hubbard, St. Louis, St. Paul and Woodburn, and a number of French Prairie historic churches.

Native Inhabitants

The Calapooya Indians were the earliest known inhabitants of the prairies. They fished at Willamette Falls, hunted game on the prairies, and picked berries in the mountains. Each fall they burned the tall prairie grass to renew their pony pastures and to round up game. There was an old Indian trail from the Molalla area to Silverton, Sublimity, across the Santiam River, and on to Klamath, with another Indian trail through the North Santiam gorge across the Cascades into the Deschutes valley. Crossings over the Willamette River were few, and limited to shallow areas—one such crossing was about three miles north of St. Paul, where the river was narrow during the summertime and a wide gravel bench.

Original Settlers

Based on the work of David Brauner, PhD, professor of archaeology at Oregon State University, we know that the French Prairie was originally populated by the Metis (pronounced “Matee”), mostly retired French Canadian trappers who once worked out of Fort Vancouver and then settled on small, French Prairie farm sites with Native American wives and large numbers of children. His research indicates that more than a decade before the first Americans found their way into the Willamette Valley, the French Prairie farms of the Metis were flourishing.

A significant number of these French Canadian-Metis employees of the Hudson’s Bay Company began settling the northern valley after their contractual obligations to the company were over so that, between 1829 and 1843, successful Metis agricultural communities developed in several locations throughout the Northwest. The oldest and largest of these was French Prairie.

“The Metis were the dominant population group in the valley, surpassing that of many of the Native American tribes whose presence in the area was ancient,” he says. “I’m convinced that when the first immigrant train arrived in Oregon City in 1843, it was not greeted by a virgin wilderness but was witness to a partially settled landscape whose population had already developed suitable agricultural strategies for the successful exploitation of the best farm land in the valley. Put simply, the agricultural industry of the Willamette Valley was already under way by 1843, which explains why the Jason Lee Mission is so close to Salem. All the good land north into French Prairie had long been taken.”

From this, Brauner draws a simple conclusion: The success of many of the first American farmsteads may well be attributed to the experience and guidance of the Metis community.

At that time, Oregon Country was a joint occupancy of the United States and British governments, and the Metis played a significant role in the transition that led to Oregon becoming part of the United States. In the older cemetery at St. Paul, the one across the road from the high school, lie the bodies of two men who claimed with some convincing evidence they were members of the Lewis and Clark Expedition … Francois Rivet and Philippe Degre. Rivet died in 1852 at age 95. Degre was 108 when he died in 1847. A grave mate of theirs is Entienne Lucier, the “Father of Oregon Agriculture.” Mr. Lucier was also one of two French-Canadians to vote pro-American at that historic meeting at Champoeg on March 3, 1843, when, by a tally of 52-50, the group agreed to form a provisional government as an important first step to Oregon eventually becoming an American state (1858). In the other cemetery, just a stone’s throw away, lies Archbishop Francis Norbet Blanchet, first Catholic Missionary to the Pacific Northwest and the priest who once had responsibility for all Catholic churches west of the Mississippi. Blanchet figures prominently in the early history of French Prairie and took the leadership role in forming the coalition of Americans and French-Canadian/Metis who helped successfully launch Oregon’s provisional government. This history and these actions laid the foundation for future agricultural development and the establishment of towns such as St. Louis, Champoeg, Gervais, and later Butteville, Donald, Aurora, Canby, etc.

The Land and The Pioneers

The destination of the immigrant wagon trains from the Eastern United States in the Oregon Country was the land east of the Willamette River and south to present-day Salem in Marion County—now referred to as French Prairie. This prairie land was fringed with forests, but the prairies themselves had few trees and little brush. Dr. John McLoughlin and one of his Hudson Bay Company employees pronounced this prairie land the Northwest’s most desirable region for settlement. According to an early day traveler, Rev. Samuel Parker, the soil was alluvial river bottom; rich, easy to cultivate, sufficiently dry for cultivation, yet well watered by small streams and springs. French Prairie is the largest of these prairies.

The early immigrants found French-Canadian (Metis) Catholic settlements. They were followed by Methodist missionaries looking for converts. Later came the Eden-seekers who arrived in Oregon by wagon train, or by ship from across the Isthmus of Panama, or around the tip of South America. Among these immigrants were families not only from the States but also from Ireland, Germany, Switzerland, and Austria. Many of their descendants are still farming here. The first settlers were subsistence farmers, raising what was needed to support a family: gardens, fruit trees, cows, pigs, and chickens.

“Old white winter wheat” was the mainstay cash crop and was the medium of exchange until the 1850s: $1 = 1 bushel of wheat. The yield was fifteen to twenty bushels an acre. Besides wheat, early Hudson Bay records show trading items of beaver skins, buckskins, salt salmon, shingles, and saw logs. By 1843 trade included cattle, horses, sheep, swine, oats, potatoes, bacon, and sides of beef. At that time the market was the Sandwich Islands, China, and the Russian settlements in Alaska. As improved transportation brought markets closer to Willamette Valley farmers, the list of crops expanded to include beef cattle, hops, berries, chickens, and turkeys and by the end of the century, many farmers were growing apples, prunes, cherries, peaches, and nuts as well.

The California Gold Rush had a great effect on the Willamette Valley. Two thirds of the men left for California, together with some women. Farms and mills were run by old men, boys, and women. Some gold seekers never returned to Oregon, some returned with nothing. Others brought back gold, which they invested in more land or became storeowners. There was a great demand for flour and lumber in the gold fields, not only in California, but also in Jacksonville, eastern Oregon, and Idaho. Prices soared. To take advantage of the heightened demand, to get more land into production, forested land was cleared, using Chinese labor and horses. Horses were used not only to pull stumps, but also to propel threshing machines, plow, take logs to mills, and crops to market.

Moving Crops to market in the early days meant that wagons were either up to their hubs in mud or dust. The settlers’ connection with the civilized world was the Willamette River, which they used for transportation of passengers and crops. They tried to locate within a day’s round trip of the river, and the first settlers located along the Willamette from Oregon City south to Salem. There were about 100 landings on the river, and farmers brought their grain to these river landings, stacked it under trees to protect it from weather and theft, then waited for canoes, flatboats, or keel boats to take their grain down to Oregon City.

Regular steamboat service began in 1851, calling at landings like Butteville, Champoeg, Fairfield, Wheatland, and Lincoln. Warehouses were built where grain and other perishables could be stored. Cattle and swine were kept in pens near the river. The two-month period following harvest was the busy time at the landings, teams and wagons waiting their turns to unload. Steamboats moved wheat downriver during the high water season, and by spring most warehouses had been emptied. The river was a mixed blessing. Many times floods carried away livestock, landings, docks, warehouses, shops, hotels, and stores. The 1861 flood, the biggest in memory, is just one of the many which afflicted Willamette Valley residents. Repeated floods in 1843, 1849, 1853, 1860, 1861, 1888, 1890, and 1894 convinced early day settlers that it was wise to build and farm at a safe distance from the river. That is the reason there are no permanent cities or towns on the Willamette between Oregon City and Salem, and none at all on the Pudding River.

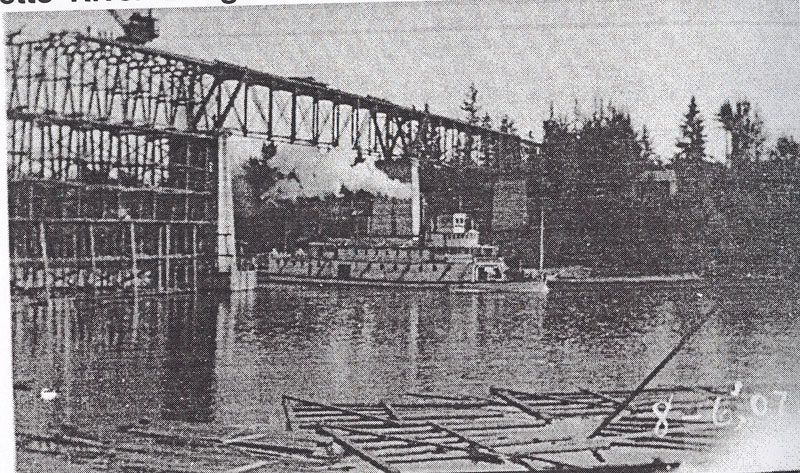

Construction of the Oregon Electric Railway Bridge over the Willamette River at Butteville in 1907, Donald Debois Collection

The railroad, supplanting the steamboat, changed the future for many communities along the river. No longer was it necessary for a farmer to live within a day’s round trip to the river. No longer was it necessary to wait for high water so boats could navigate. The landings along the river disappeared. The railroad became the artery of trade. In 1869 a north-south railroad from Portland via Aurora-Woodburn to Waconda was established. An east-west railroad from Ray’s Landing (across the Willamette from Dayton), through St. Paul and Woodburn, to Silverton never materialized. With the advent of the railroad, wheat production and cattle grazing moved across the mountains to central Oregon but the railroad brought markets and processors closer to Willamette Valley farmers. Roads. The paved road finally got the farmer out of the mud.

Marion County

Most of French Prairie is within Marion County. It was originally named Champooick District (later Champoeg) and was created on July 5, 1843 by the Provisional Legislature. At that time Champoeg District stretched southward to the California border and eastward to the Rocky Mountains. The area, however, was soon reduced with the creation of Wasco, Linn, Polk, and other counties. Marion County’s present geographical boundaries, established in 1856, are the Willamette River and Butte Creek on the north, the Cascade Range on the east, the Santiam River and North Fork of the Santiam on the south, and the Willamette River on the west. Marion County shares political borders with Clackamas, Yamhill, Polk, and Linn Counties. The county contains 1,194 square miles. Champoeg District was redesignated a county in 1845 and renamed Marion County in 1849 after General Francis Marion, a Revolutionary War hero. That same year Salem was designated the county seat.

More Communities

Get Involved Today!

Promoting prosperous farming requires work in many areas to develop brand recognition, help local farmers find and develop new markets and connect with new opportunities—as well as preserving farm land. As new and varied demands for land arise, careful management and strong advocacy will be necessary to ensure that important values are observed and strengthened.

Together we can guide development of the French Prairie area. We need your help, and we need your donation—today!